Can college admissions be race-neutral?

Lucas Spielfogel is a graduate of Yale University and the author of The College Playbook. He has served as BRYC’s executive director since 2012.

By Lucas Spielfogel

In the days since the Supreme Court outlawed the inclusion of race in college admissions, many have argued that relatively few students will be affected by the ruling, since selective colleges – those that most consider applicants’ race – enroll just three percent (480,000) of our country’s 15.4 million undergraduate students.

There’s truth in this. Most Black and Brown students won’t apply to or attend selective colleges, so we should be more concerned with how they’re faring in higher education generally, rather than with their slim odds of getting into Harvard. So how are they faring?

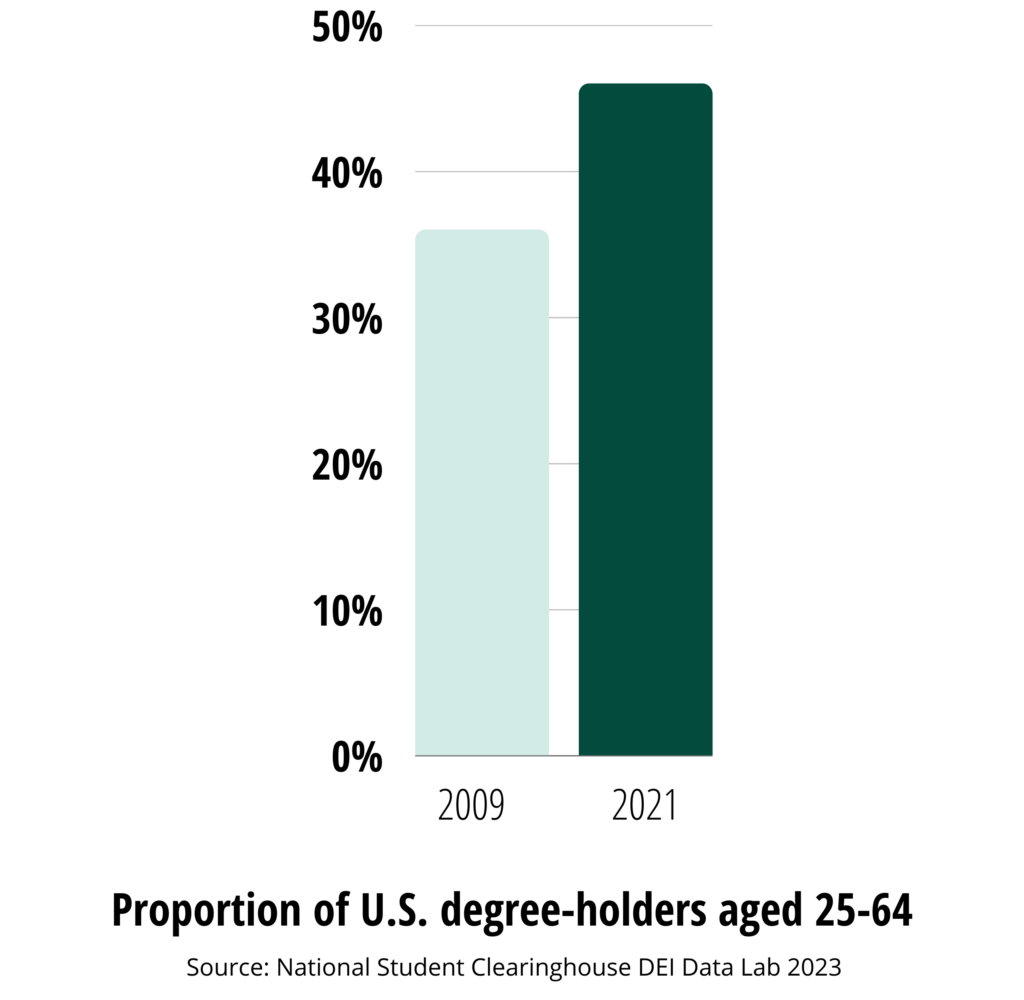

The good news is more Americans of every race are earning college degrees which, despite their backbreaking cost, remain engines of economic mobility. Between 2009 and 2021, the proportion of Americans aged 25 to 64 with two- and four-year degrees rose from 38 to 46. But racial gaps in college completion remain concerning.

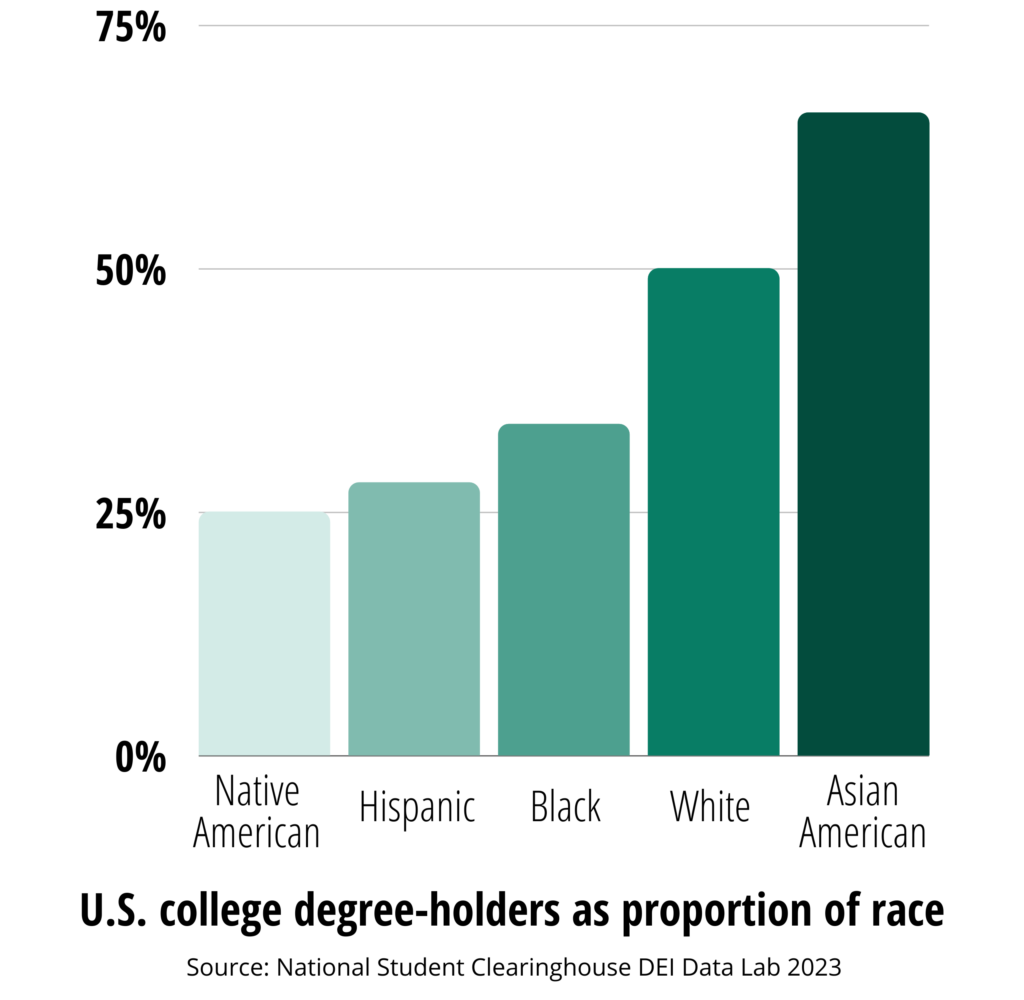

In 2021, about 66 percent of Asian American adults and 50 percent of white adults held degrees, while Black, Hispanic, and Native American adults came in at rates of 34, 28, and 25 percent, respectively. One would hope for these gaps to narrow over time, anticipating newly-minted graduates to make up for universally low degree attainment among Americans over 35, but that isn’t happening.

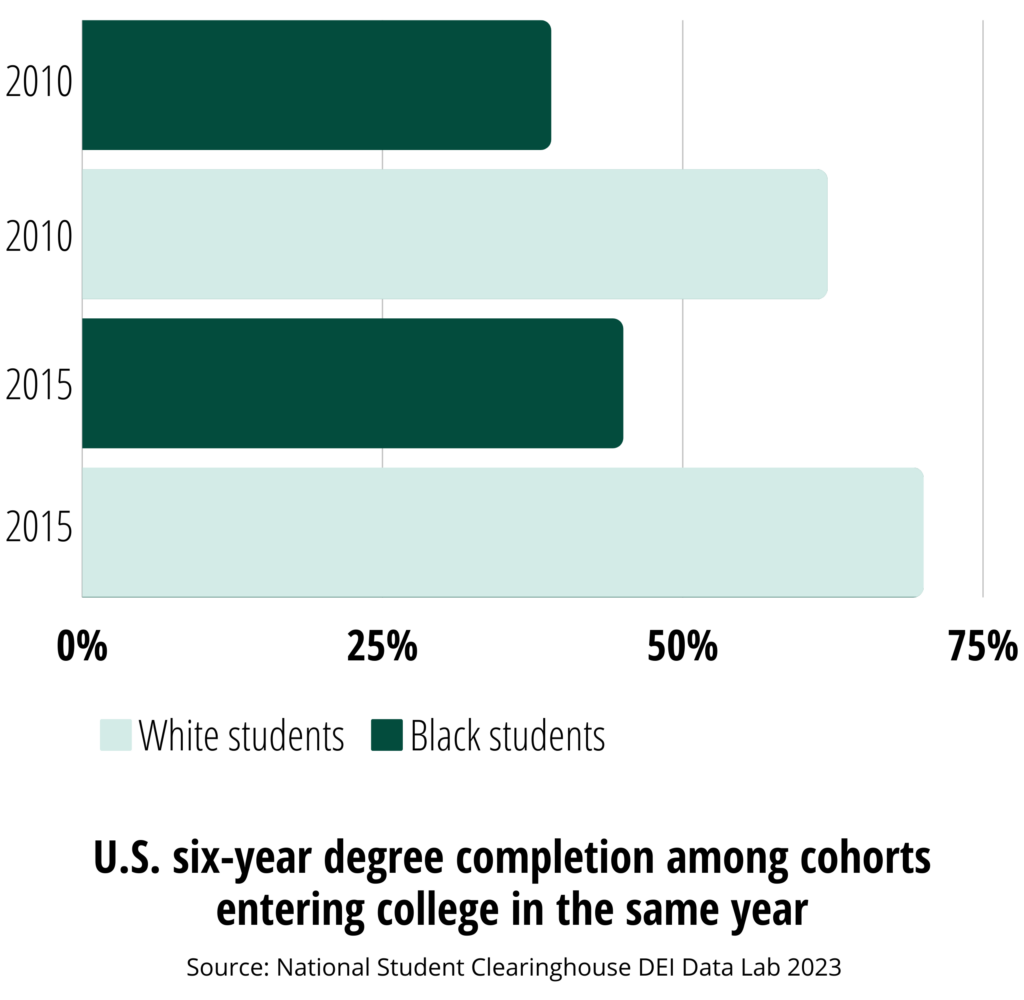

The National Student Clearinghouse’s DEI Data Lab tracks six-year degree completion among cohorts who entered college at the same time. Among those who began in fall 2010, white and Black students earned degrees at rates of 62 and 39 percent, respectively. In the 2015 cohort, overall completion improved, but the race gap expanded, with white students finishing at 70 percent to Black students’ 45.

Why are Black and Brown students struggling so much to secure the very thing we promise ensures a better life? Is it because they are inherently inferior to their Asian American and white peers? I pray that no one reading this believes that. No, it’s because they are suffering the multi-generational consequences of our nation’s fraught racial history and our collective fear in confronting it.

The Supreme Court’s demand for “race-neutral” college admissions can only be called unrealistic when race so heavily influences a student’s ability to realize college success.

I was once oblivious to these consequences. They were abstract to me since, prior to moving to Baton Rouge in 2010, I had never had any meaningful exposure to being Black or Brown in America, including and especially during my time at Yale. I feel comfortable assuming that the people behind Students For Fair Admissions (SFFA), whose 2014 lawsuit against Harvard and University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill spurred the Supreme Court’s ruling, have had similarly limited opportunity to see outside their experience. This also applies to people in my life, including friends and loved ones who have alleged that Black and Brown students have an “unfair advantage” in college admissions. This claim has always confused me, not because I judge anyone for wanting the best chance at attending their dream college, but rather because I can’t imagine they would want to trade places with my students in that pursuit.

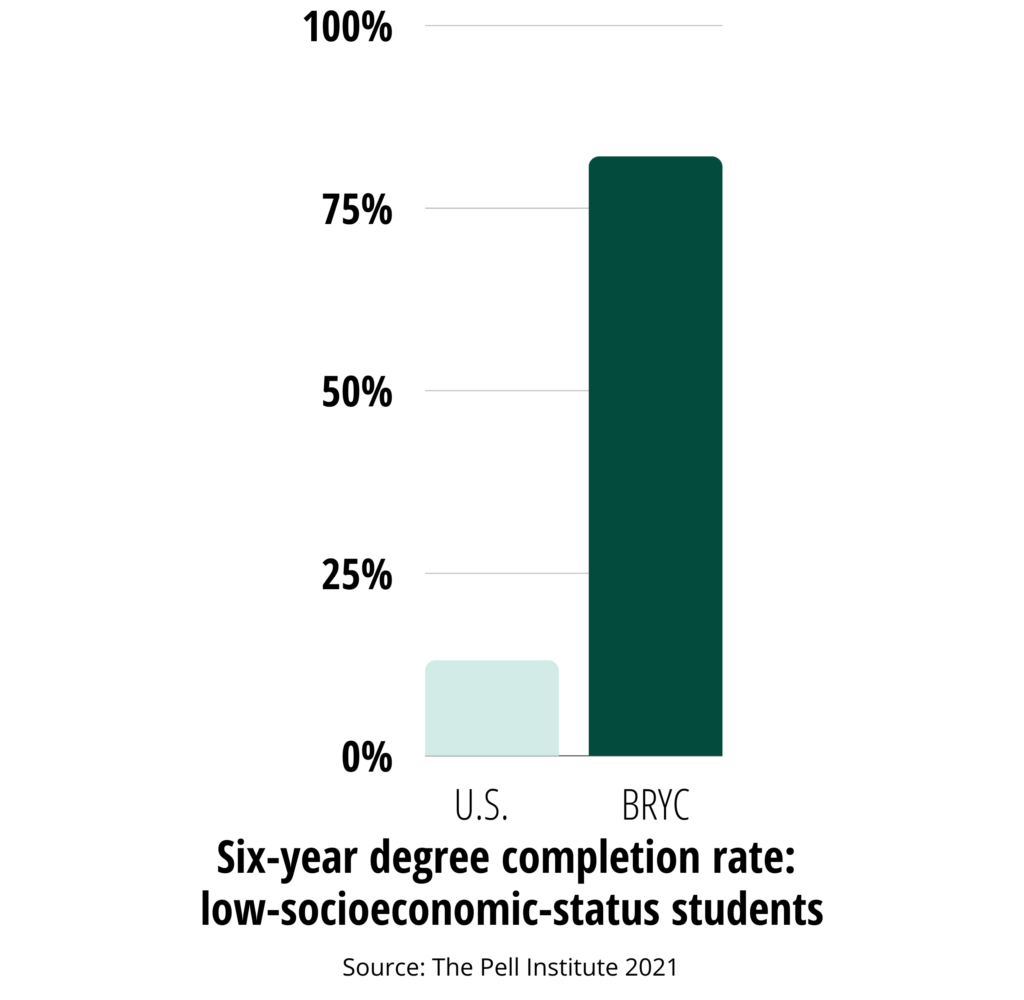

At the Baton Rouge Youth Coalition (BRYC), we have spent the last 14 years building a support system that helps primarily Black and Brown students from low-socioeconomic (low-SES) backgrounds enter and graduate from college and convert their degrees into jobs. With 11 years under my belt, I could say that, without an intervention like BRYC, this journey is almost impossible, but the data say that for me: only 13 percent of American students from low-SES backgrounds earn bachelor’s degrees.

White and Asian American students come from low-SES backgrounds, for sure, just not nearly as often as Black and Brown students, who therefore are significantly more likely to attend schools lacking in rigorous instruction, standardized test prep, and meaningful attention from a counselor, who could be supporting up to 400 students at a time. Under-resourced schools offer fewer well-organized enrichment opportunities to tout on college applications, and if there are such opportunities, Black and Brown students often can’t enjoy them, as they are disproportionately expected to hold jobs or care for younger or elderly relatives. I have seen again and again how this razor-thin resource margin minimizes time and maximizes stress, conditions under which pursuing college takes a backseat to surviving.

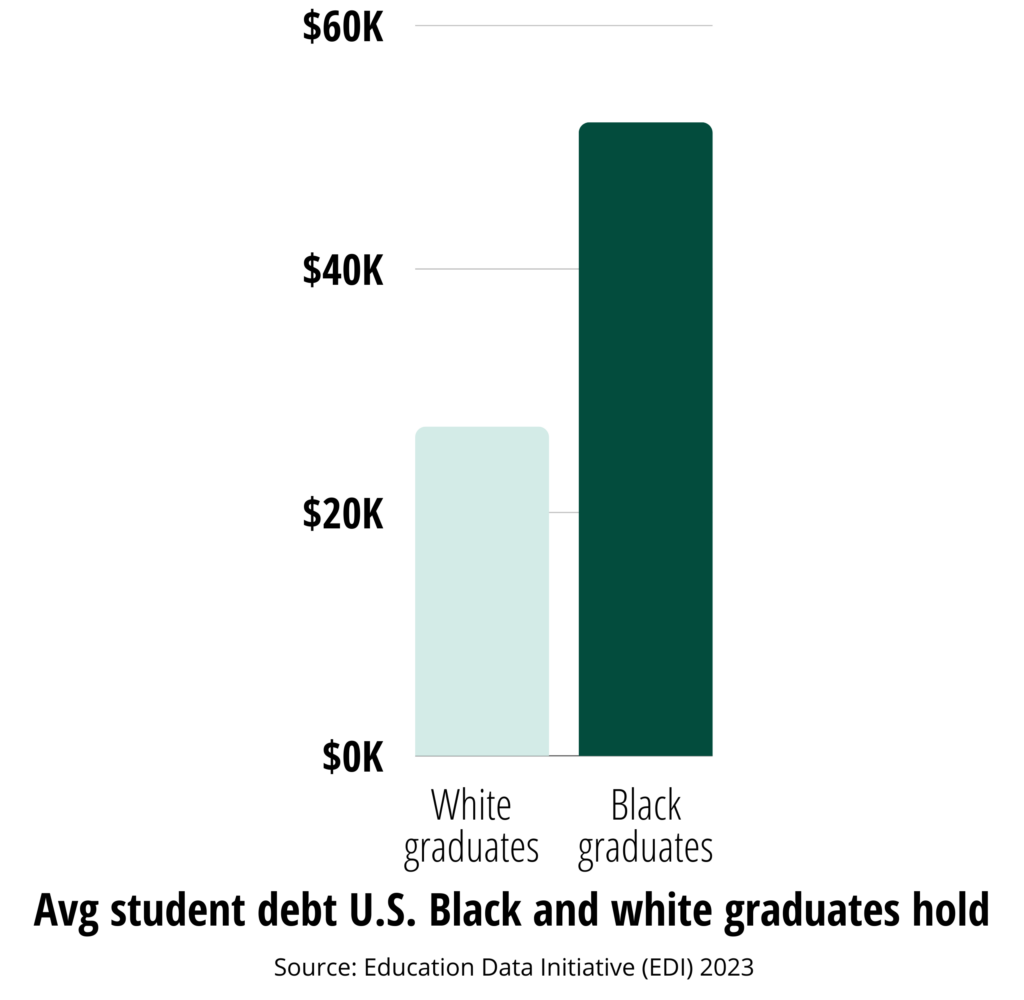

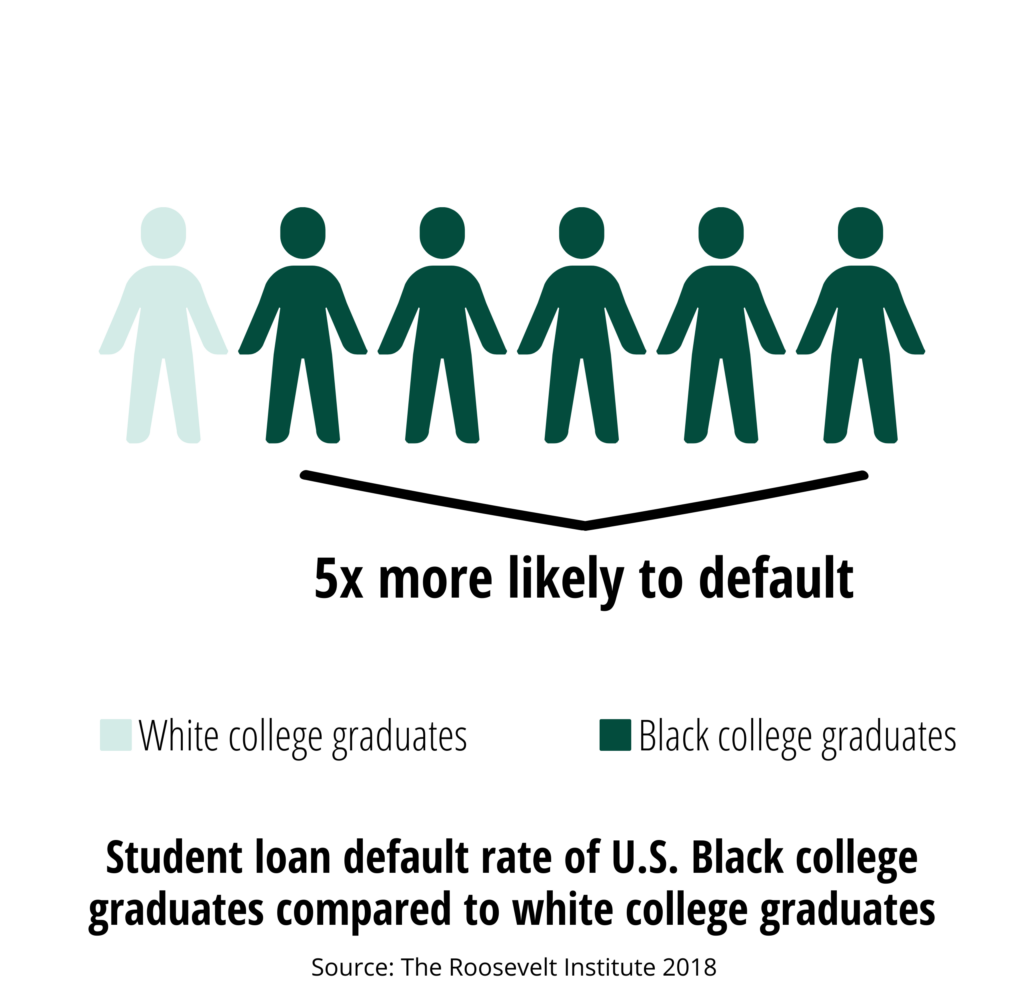

And yet, through sheer force of determination, many of these students enter college, where similar challenges await. In a 2023 joint study by Gallup and the Lumina Foundation, it was reported that Black students are twice as likely as any other student to have caregiver responsibilities and be employed full time, and the Education Data Initiative reports that Black students owe an average of $25,000 more in student loan debt than white students, leading Black college graduates to default at fives times the rate of white graduates. Despite being in this work more than a decade, I still struggle to understand how students in this position stay the course. BRYC Alumna Amber Richardson, a 2022 Southern University graduate, said it best: “No matter how ‘resilient’ or ‘gritty’ we are – and trust me, I am both – the larger-than-life stress and fear of these moments make letting go feel legitimately like the right choice.” As a registered nurse at the Baton Rouge General, Amber knows too well that Black and Brown Americans fare far worse against all social determinants of health, not just education access and quality.

The Supreme Court’s demand for “race-neutral” college admissions can only be called unrealistic when race so heavily influences a student’s ability to realize college success, and the assertion that the ruling impacts relatively few can only be called shortsighted. It’s not only that enrollment of Black and Brown students from low-SES backgrounds will drop at selective institutions which are proven drivers of economic opportunity. More importantly, the ruling communicates to underrepresented students of all academic levels that higher education doesn’t care what you went through to get here, what unique contributions you bring to bear, or how we can best support you. Trust me: that message didn’t need to be reinforced. I fear it will greatly reduce enrollment – which remains 1 million below pre-pandemic levels – and worsen already-dire labor shortages.

Hundreds of colleges have disavowed the ruling because they understand that alienating these students will lead to culturally sterile campuses and, worse, subpar learning. An educational environment that doesn’t reflect the diversity of real life isn’t much of an educational environment at all. Even the Supreme Court knows this, evident in its exclusion of U.S. service academies from race-neutral admissions as a way to ensure diversity across ranks, which military leaders say is crucial for building effective fighting forces. It’s silly to claim this logic doesn’t apply in any other setting. Indeed, the exemption of military academies undercuts the Court’s core legal rationale that the benefits of diversity aren’t clear enough, when they are, evidently, clear as life and death.

“No matter how ‘resilient’ or ‘gritty’ we are – and trust me, I am both – the larger-than-life stress and fear of these moments can make letting go feel legitimately like the right choice.” – Amber Richardson, BRYC alumna, Baton Rouge General

Although that rationale prevailed, I don’t believe it reflects our nation’s prevailing view. I believe most of us want to live in a country where expansive access to high-quality education activates the innate assets of all young people, where talent abounds to tackle problems keeping us from our collective best. And I believe most colleges embrace their role as guardians of the American Dream and therefore will seize this opportunity to reexamine their relationship with underrepresented students. This should start with reaching much deeper into underserved areas – including strengthening partnerships with organizations like BRYC – and it should lead to a reimagined admissions process that yields the sort of authentically diverse learning community where empathy thrives. In that light, I invite you to join our community. There’s no better way to ally with our youth than to become a BRYC mentor, and there’s no better time than right now.